03.13.10

Posted in General News, Weather News at 11:28 am by Rebekah

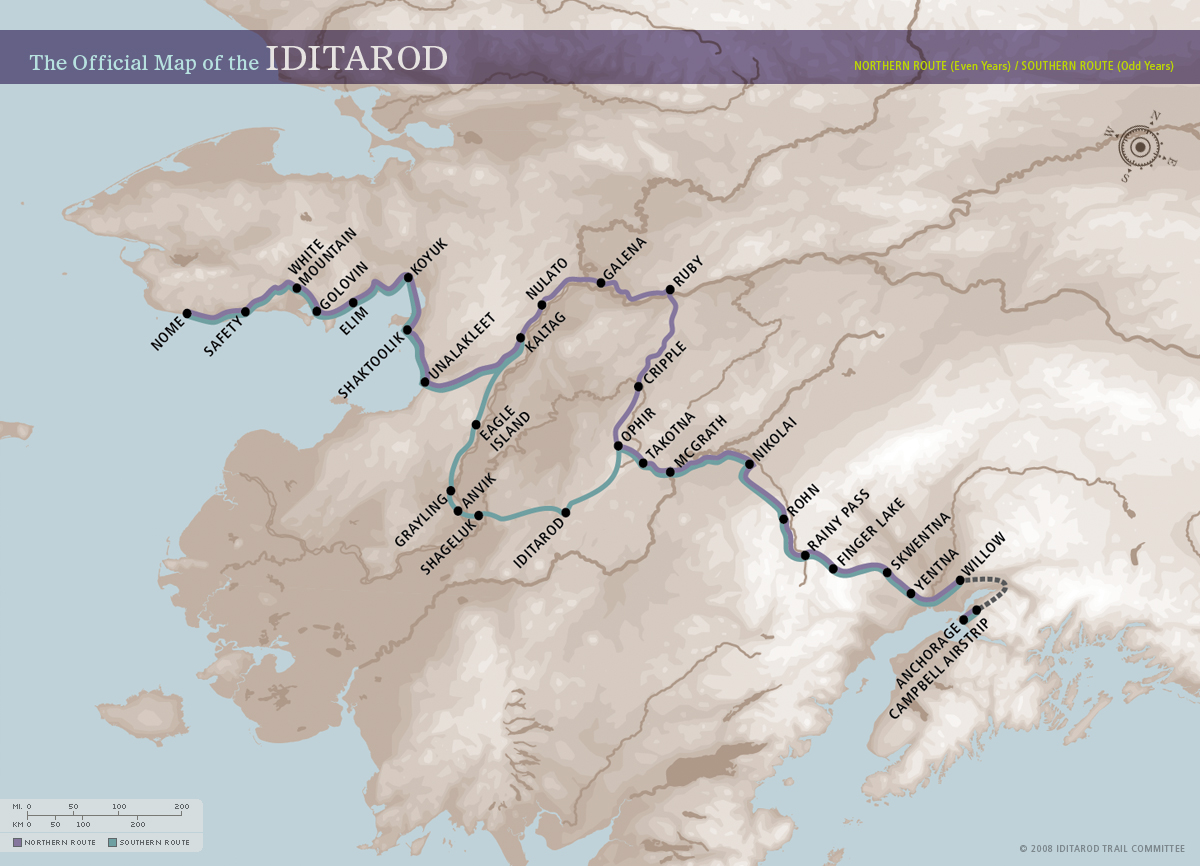

The Iditarod Trail Sled Dog Race is underway in Alaska.

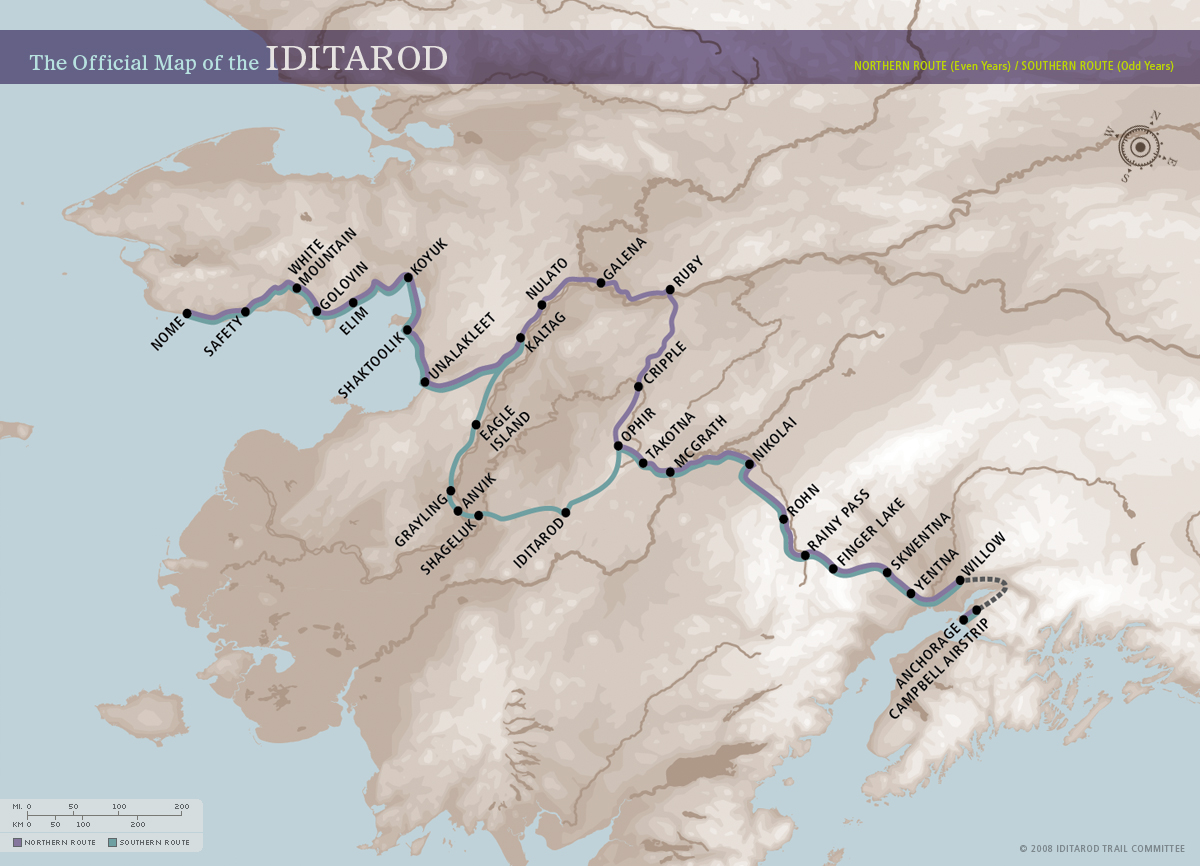

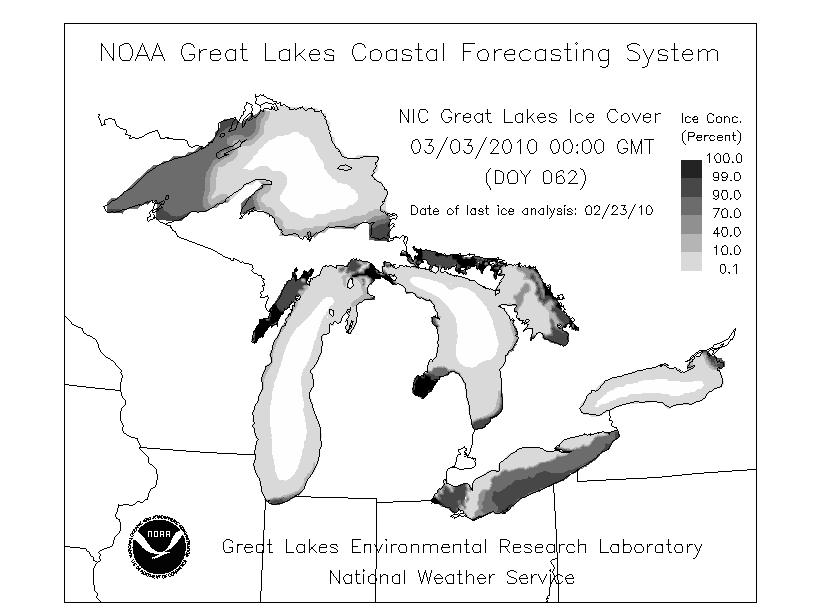

Last Saturday, 71 teams set out from Anchorage on their approximately 1,100-mile-long journey to Nome. As of today, the leading musher, Jeff King, is well over halfway done with the race.

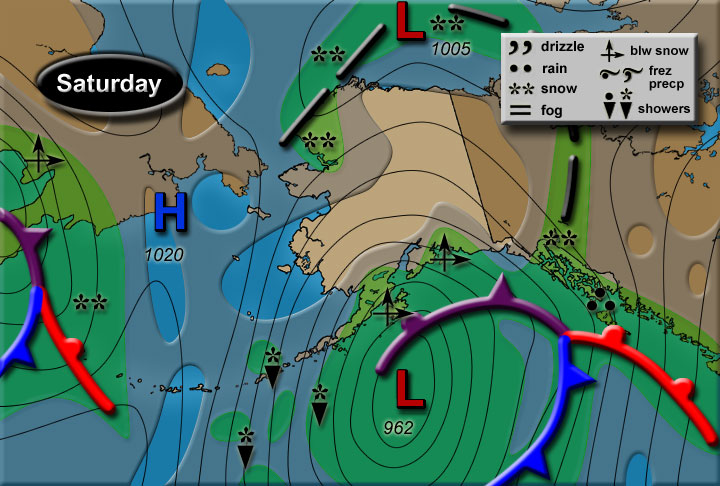

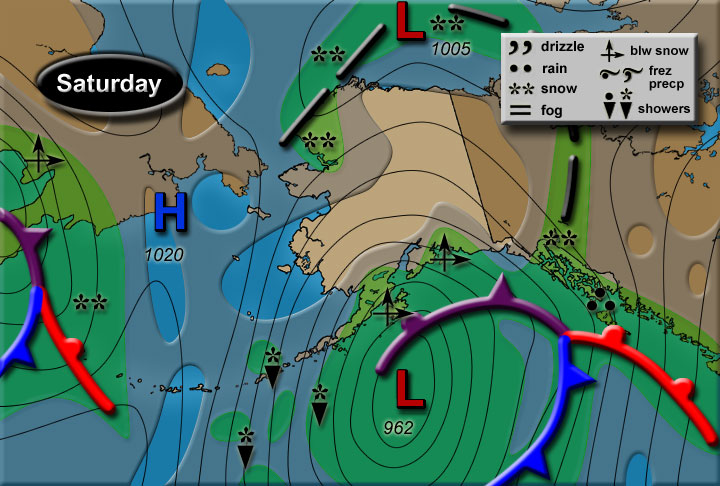

Although there is currently an extratropical cyclone in the Gulf of Alaska, it looks like snow and blizzard conditions will be limited to southern Alaska. On the other hand, there will be no shortage of cold weather for the mushers and dogs!

It’s currently 28 below in Nome, and the NWS is calling for a high today of 10 below. Yesterday, tonight’s low was forecast to be 25 below with a wind chill of 50 below, but today it’s been updated to only 20 below with a wind chill of only 40 below! No wonder most of the mushers come from Alaska–there are probably few other people that could withstand the cold. 🙂

According to the National Climatic Data Center, Nome’s average high in March is 17.7 °F and average low is 0.5 ºF. The record cold temperature for Nome, not including wind chill, is -54 ºF (records date back to 1900).

For more information on the Iditarod, and up-to-date information on the current standings and location of the teams, check out the official site of the Iditarod.

Iditarod route; this year the teams are taking the northern route. Courtesy of The Official Site of the Iditarod.

Alaskan weather forecast for today. Courtesy of the National Weather Service in Anchorage.

Permalink

03.11.10

Posted in Weather News at 4:12 pm by Rebekah

Severe weather is still occurring in Florida this afternoon, where at least one more tornado has already been spotted. Severe storms and steady rain are expected to continue for the next few days along the East Coast. What’s going on?

On Sunday, a shortwave trough entered California from the Pacific. By the time the surface low pressure system associated with the trough moved into southern Colorado Monday morning, the low had started to occlude. A surface low, a.k.a. extratropical or mid-latitude cyclone, generally starts to weaken when its cold front catches up to its warm front. Cold air is more dense than warm air, so it moves faster and eventually catches up to the warm front; this process is called occlusion. The tornadoes in Oklahoma on Monday occurred near the point of occlusion.

The last couple of days there has been some severe weather in the warm sector of the slow-moving cyclone; this is the relatively warm area between the cold front and warm front, south of the occluded front. Unfortunately the cyclone isn’t going anywhere fast, as eventually it will become completely occluded and just sit and spin away from the fronts.

I took a look at the GFS and NAM models today and noticed the ridge in the west and the ridge in the east are building and expected to merge above the upper-level low. This results in a large ridge of high pressure situated above a closed low. The GFS model further shows that a closed high may develop within the ridge, directly above the low. This is called a high over low block, or a “rex” block. There are several blocking patterns that frequently occur, all of which prevent pressure systems from quickly moving across an area. This particular type of block means that air will flow in an S-shape, clockwise around the high and then back counter-clockwise around the low. In other words, the low is in no hurry to go anywhere, and will only bring more rain to the East Coast (especially the Northeast). It looks like the rex block will be strongest over the weekend, before breaking up and allowing the low to progress out into the Atlantic.

GFS model forecast for Sunday at 12Z, at 500 mb, showing the ridge/high above the low in the mid-levels of the atmosphere:

The GFS model also is starting to show a potentially decent severe storm setup over southern Kansas and Oklahoma next Friday…that’s still over a week away, so it will likely change by quite a bit. It may be an interesting setup to watch, though…

Permalink

03.04.10

Posted in Weather News at 3:05 pm by Rebekah

As an update to my post a couple days ago, in which I said no tornadoes were reported in the US in February for the first time since records began around 1950, I stand corrected. A late tornado report made it in to the San Joaquin Valley/Hanford NWS office.

This EF0 tornado was reported by a trained storm spotter near Taft (near Bakersfield) in southern California on February 27th. It reportedly lasted 3 minutes and did not cause any damage.

However, this was still a remarkable month, as only two or three times has February seen only one or two tornadoes since 1950 or so!

Permalink

03.03.10

Posted in Weather News at 4:00 pm by Rebekah

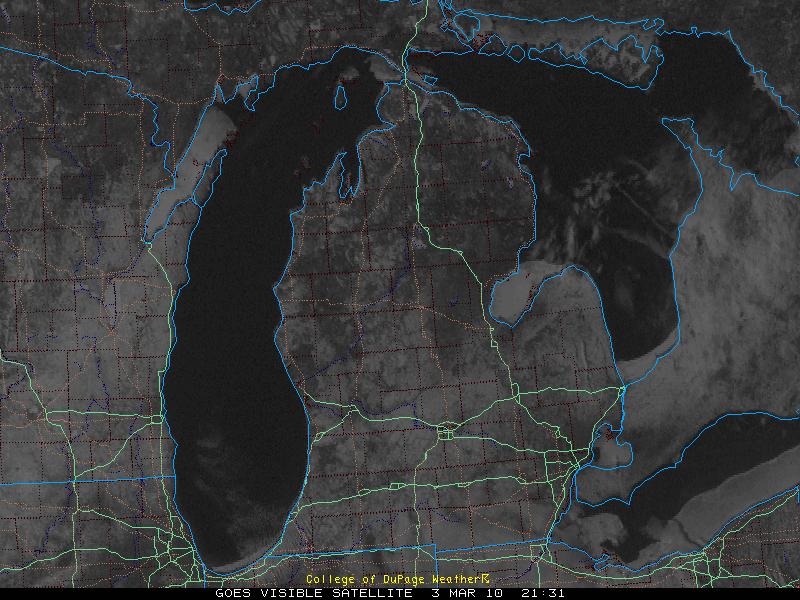

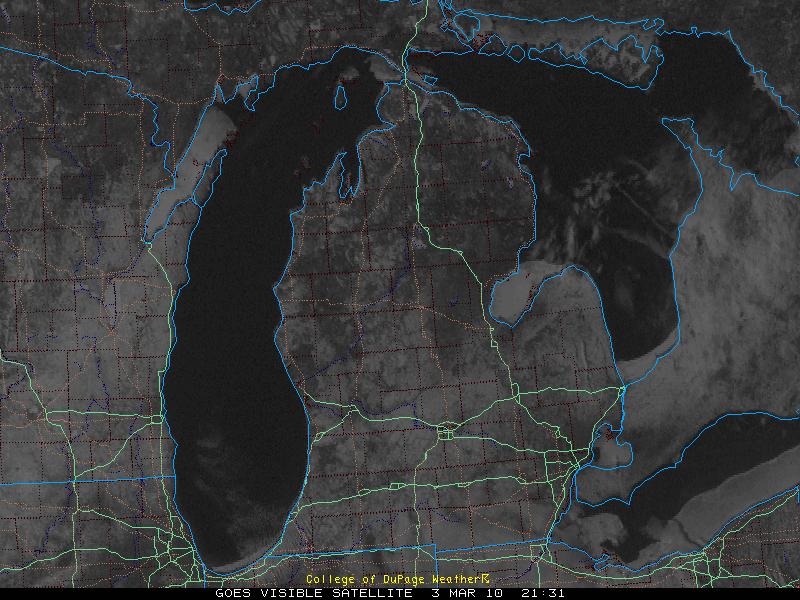

While browsing some visible satellite images this afternoon, I came across a cool- but strange-looking image of Lake Michigan. Green Bay (the bay, not the city) appeared to be socked in with clouds, but the “clouds” weren’t moving on a satellite loop. If I saw this over land, I might think it were snow or fog.

A visible satellite image is just what it sounds like. A satellite records visible light reflected off the earth by the sun, so what you see on the satellite image is what you would see from space. White areas indicate a lot of reflected light (e.g., thick clouds or snow) while gray areas indicate less light (e.g., thin clouds). Snow is often visible on these satellite images.

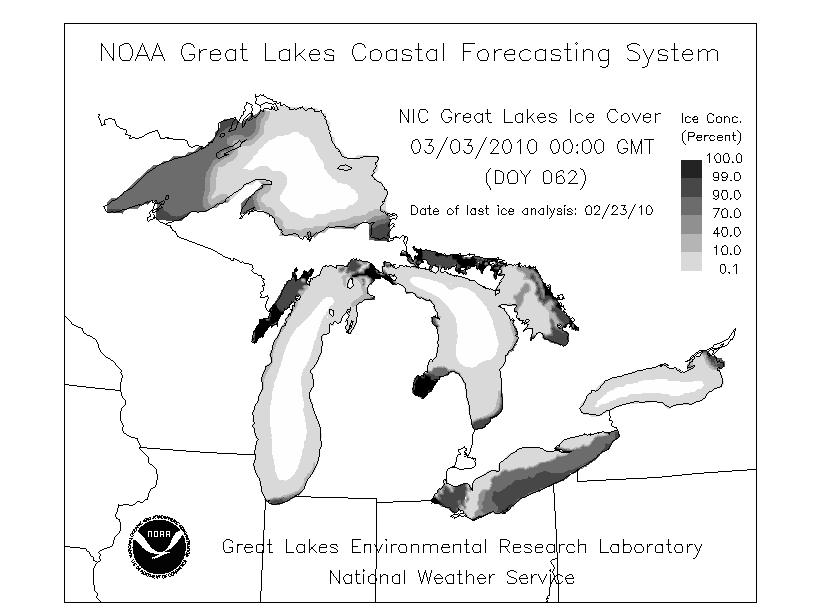

When I looked at a nearby satellite image, I saw what appeared to be ice over part of Lake Erie. Lake Erie recently froze over, but now the ice is starting to break up and melt. After looking at a map showing current ice cover over the Great Lakes, I confirmed that the ice was indeed showing up on the visible satellite images. There might even be some snow on top of the ice.

Visible satellite image over Michigan, courtesy of the College of DuPage. To view more satellite images such as this (as well as loops), go to http://weather.cod.edu/analysis/analysis.1kmvis.html

Great Lakes ice cover, courtesy of the NOAA Great Lakes Coastal Forecasting System. To view this and other maps of the Great Lakes, see http://www.glerl.noaa.gov/res/glcfs/

MODIS satellite image of Lake Erie, showing ice cover on February 20, courtesy of the NWS in Buffalo. For more MODIS images of Lake Erie, go to http://www.erh.noaa.gov/buf/lakeffect/ice0910/index.htm

Permalink

03.02.10

Posted in Weather News at 4:13 pm by Rebekah

For the first time in 60 years, no tornadoes were reported in the United States in the month of February.

I’m not certain how many tornadoes the US sees on average each February; I tried to find this statistic in some weather archives, but was unsuccessful. A BBC article claims there are, on average, 22 tornadoes in the US in February; however, considering the same article says that tornadoes form when cold air collides with warm air, I would not completely trust this source.

One of the most perpetuated myths about Tornado Alley states that tornadoes form because of collisions between airmasses. Few myths grate on my nerves more than this one.

An airmass is a large body of air whose properties (e.g., temperature and humidity) are fairly uniform. These airmasses may be thousands of kilometers across and up to several kilometers high. The boundaries between these airmasses are what we call fronts, and that’s where a lot of our interesting weather takes place. If a cold airmass dives south from Canada into the US, the leading edge of the airmass is a cold front. If a warm, moist airmass moves north from the Gulf of Mexico into the US (i.e., cold air retreats northward ahead of the warm airmass), the leading edge of the airmass is a warm front.

If tornadoes occurred whenever airmasses collide, the entire world would be in a lot of trouble–as airmasses collide globally all the time, no matter what season it is. Furthermore, with all of the cold fronts that we’ve had over the past few months, February should have been full of tornadoes in the US.

The primary conditions for strong thunderstorm (and possibly tornado) formation are lift, instability, low-level moisture, and wind shear.

Thunderstorms require rising air, and lift gets the air to start rising. Lift may come in the form of a front, a dryline (similar to a front, it is the leading edge of a dry airmass, preceded by a moist airmass), a surface low pressure system, solar heating, an upper-level trough of low pressure, etc.

Once the air starts to rise, an unstable atmosphere will ensure that the air keeps rising. Air cools as it rises, but as long as it doesn’t cool as fast as the surrounding environment (i.e., the rising air is warmer than the environmental temperature), we have an unstable atmosphere. The best setup is one in which the environmental temperature is warm at the surface and rapidly decreases with height.

If the rising air is dry, we probably won’t get any clouds–so we want to have a warm, moist environment near the surface. The higher the moisture content, the more likely it is that we will have low-based clouds (good for tornadoes).

Finally, in order to get long-lived, rotating thunderstorms, called supercells, we also need to have the wind increasing and changing direction with height. This is called wind shear.

During the month of February, we had plenty of lift and shear, but not enough instability or moisture for many severe thunderstorms. We continue to be in an active weather pattern in terms of upper-level troughs and a strong southern jet stream, but the Southern Plains needs to heat up and moisture needs to return before we can have any hope of the storm chasing season beginning.

When will this happen? According to long-range weather and climate index models, it looks like it may be at least another couple weeks.

Permalink

« Previous Page — « Previous entries « Previous Page · Next Page » Next entries » — Next Page »